The most profound realization of Zen Buddhism teaches that “self” or “soul” is an illusion. The famous Zen master Obaku came to a great realization upon hearing these words from a sutra: “Cultivate the Mind that does not have a fixed abiding place.”

As children, we live this way without even thinking about it. That is why, as adults, we long for that seemingly lost purity of childhood.

How often have we seen small children completely “lost” in their games, and how we almost hate to call them by name, to “bring them down to earth” by reminding them to go to bed or whatever? As children, we easily have this ability to move freely in and out of situations. However, as we get older — because of bad habits and erroneous training — we get fixated on the idea of a separate, solid self.

This feeling of a fixed self is born when we are small, by saying “no” to whatever situation surrounds us. But, as long as we give ourselves over completely to our circumstances, there is no problem. That is why we have an easier time when things are pleasurable: the ego does not resist so much.

For example, let’s take the situation of cleaning up after a meal. Usually, when we are washing dishes at the kitchen sink, only about 60% of our being is actually involved with the glasses, soapsuds, and water; the other 40% is daydreaming about all kinds of things.

That 40% “residue” not involved with the activity at hand gives us the feeling that there is some kind of a fixed self doing these various things. We live most of our adult lives this way, never completely giving our entirety to whatever we do. We “sit on the fence,” so to speak, neither passively letting our world completely permeate to our very core nor completely giving ourselves over to whatever activity we are involved in.

There always seems to be this “leftover” residue that stands back to comment, complain, and evaluate while we are doing something else. By the time we reach adulthood, most of us don’t even question who this so-called “self” is; we just take its existence for a real, solid thing. Then we worry about its well-being, happiness, and ultimate death.

This is where Zen practice becomes vital. In formal Zen training, we first learn zazen: sitting meditation, which teaches us to quiet the mind and let the sediment settle, so to speak. When we first try zazen, we soon realize how totally out of control, noisy, confused, and erratic our mental function is. The deeper our zazen becomes, the more this “monkey mind” slows down. We find ourselves lost in the singing of the birds, or we find that, without thinking, we are together with the wind rustling the leaves on the trees.

We also learn chanting. This is a very important Zen practice that should be emphasized more than it is. When we chant, we should give our complete being over to pulling the sound up from our very core and from the very bottom of our being. No room should be left for any of that “residual percent” that stands back and comments on our activity.

However, if we think that the only time we practice Zen is when we are in a retreat, at a zendo, or doing formal sitting zazen, then we do not truly understand what real Zen life is all about. To become a monk or nun and to retire from “the world” is one way of practicing Zen, but it is rather one-sided and unbalanced. Shakyamuni himself, after many years of meditation practice, having gained his deep realization, came down from the mountain and started to practice his realization by teaching and helping other people.

One of the most complete and natural ways to practice Zen is through family life. When we look at the way formal training is set up at a Zen center, we can clearly see the usefulness of the family structure in practice.

In the zendo, for instance, the jikijitsu (meditation leader) could be compared to the head of the family — the Father — who, by his very sternness, will teach us to develop our willpower and latent strength. The shoji (the one who sits by the entrance) is the Mother, caring and compassionate, who takes care of everyone’s aches and pains and gets up earlier than anyone else in the morning to make tea. The tonto (who sits opposite the jiujitsu) is usually an older student, strong in silent wisdom, and could be likened to the Grandfather. Opposite the shoji sits the tenzo — who hardly has time to sit as she is the cook and spends most of her time in the kitchen. The tenzo could be likened to the Grandmother, who actualizes her love by ensuring that everyone is fed well with healthy, wholesome food.

There are other officer roles in a Zen center. The shika is the head of the center and takes care of all the official business, raising money, public relations and overall harmony of running the center. This position is more like the head of a corporation. Other positions in the center could probably be likened to aunts, uncles, etc. All the students without an official position are like children. The regular student’s role is to respect and honor all the officer positions, cooperate, and not cause trouble by asserting their individual wants too much. Each position must be practiced with complete dedication, love, and care.

It is very important to respect all the positions, as there is no ultimate hierarchy. If the individual ego is too strong in one position, it will unbalance the whole family structure. To help teach this lesson thoroughly, all the roles are rotated every six months—if you were the shika the last time, you might find yourself cooking the next.

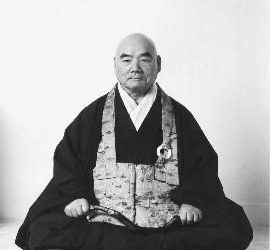

Of course, the role of the Roshi is a special position. A great Roshi could be seen as a super parent. His whole life is dedicated to teaching his students, which he does with great skill, incredible vitality, and wisdom. He is quite ruthless in questioning and resting the clarity of his students’ insights. His personal possessions are few, and he lives by the love and support of his students.

Now, if even a Zen center copies the family in its training style, we can honestly see what a fine environment the family must be for our everyday Zen practice. Unfortunately, in modern times, we have rather neglected to respect and honor this structure. We seem to have forgotten the importance of each and every role. Some may view this as old-fashioned, but from the Zen point of view, the family structure is the perfect circumstance in which we can practice and develop as Zen practitioners. The Father, Mother, Grandmother, Grandfather, and children can all be seen as positions where the individual ego is not stressed because each person, out of love for the others, will behave in a way that is good for the whole.

There is a wonderful old custom where, when you are drinking with your friend, you do not fill your own glass but your friend’s and vice versa. Neither one goes thirsty, and both parties simultaneously experience gratitude and generosity. So I ask you: where is the space, here, for “My rights! My freedom! My identity!”?

There are other numerous situations that are ideal for deepening our practice. What I mean by practice is this activity of throwing this “sitting on the fence” ego completely into whatever activity we are involved with. Our ordinary everyday life is full of occasions to do so if only we abstain from picking and choosing.

So, please — if you really want to learn and practice true Zen, just throw this troublesome, illusionary ego into the very next activity that presents itself.